London mayor: The Sadiq Khan story

Labour's Sadiq Khan has been elected as London's new mayor - but who is the man who will be in charge of the UK's capital city for the next four years?

Sadiq Khan's life to date has been characterised by beating the odds - which is what he has just done to become mayor of London.

When Labour politicians put themselves forward to run for mayor last year, Mr Khan was far from being the favourite. The bookies' money was on Baroness Jowell, a veteran of the Tony Blair years who had helped bring the Olympics to London.

But if there is a pattern in Mr Khan's career, it's one of coming from behind.

The new mayor did not have a privileged start in life. He was one of eight children born to Pakistani immigrants, a bus driver and a seamstress, on a south London housing estate.

From an early age, he showed a firm resolve to defy the odds in order to win success for himself and the causes important to him.

That resolve has won him the biggest personal mandate in the UK, a job with wide-ranging powers over London and with enormous emotional significance for him.

Some question whether he has the experience or record of good judgement necessary for the role.

He insists he is there to represent all Londoners and to tackle inequality in the capital, and now he has the chance to prove it.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Age: 45

Marital status: Married with two daughters

Political party: Labour

Time as MP: Has represented Tooting in south London since 2005

Previous jobs: Human rights solicitor, chair of Liberty

Council estate beginnings

Sadiq Khan

Sadiq Khan

"Son of a bus driver" became one of the most hackneyed phrases in Mr Khan's time on the stump - so overused in his leaflets and speeches that he was eventually forced to make fun of his own campaign, joking he had given the Daily Mirror an "exclusive" on his background.

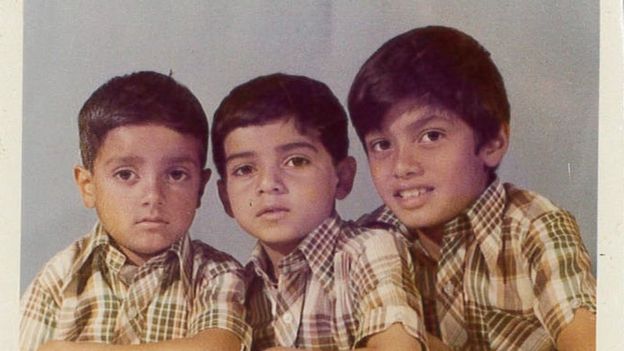

But his parents' story holds real significance for him. Amanullah and Sehrun Khan emigrated from Pakistan to London shortly before Sadiq was born, in 1970. He was the fifth of their eight children - seven sons and a daughter.

He has often said that his early impressions of the world of work shaped his belief in the trade union movement. His father, a bus driver for 25 years, "was in a union and got decent pay and conditions" whereas his mum, a stay-at-home seamstress, "wasn't, and didn't".

He lived with his parents and siblings in a cramped three-bedroomed house on the Henry Prince Estate in Earlsfield, south-west London, sharing a bunkbed with one of his brothers until he left home in his 20s.

He attended the local comprehensive, Ernest Bevin College, which he describes as "a tough school - it wasn't always a bed of roses". The nickname "Bevin boys" was at that time in that part of south London a byword for bad behaviour.

It was at school that he first began to gravitate towards politics, joining the Labour Party aged 15. He credits the school's head, Naz Bokhari, who happened to be the first Muslim headteacher at a UK secondary school, with making him realise "skin colour or background wasn't a barrier to making something with your life".

Mr Khan was raised a Muslim and has never shied away from acknowledging the importance of his faith. In his maiden speech as an MP he spoke about his father teaching him Mohammed's sayings, or hadiths - in particular the principle that "if one sees something wrong, one has the duty to try to change it".

Getty Images

Getty Images

He was an able student who loved football, boxing and cricket - he even had a trial for Surrey County Cricket Club as a teenager. He has since spoken about the racist abuse he and his brothers faced at Wimbledon and Chelsea football matches, saying he felt "safer" watching at home and became a Liverpool fan simply "because they were playing such great football at the time".

He studied maths and science at A-level with the idea of becoming a dentist. He was switched on to law by a teacher who told him "you're always arguing" - and by the TV programme LA Law, starring Jimmy Smits as Victor Sifuentes, a charismatic partner in a California law firm.

"LA law was about lawyers in LA who do great cases, act for the underdog, drove nice cars, look great and I wanted to be Sifuentes," Mr Khan told Business Insiderrecently.

Sadiq Khan

Sadiq KhanCourtroom crusader

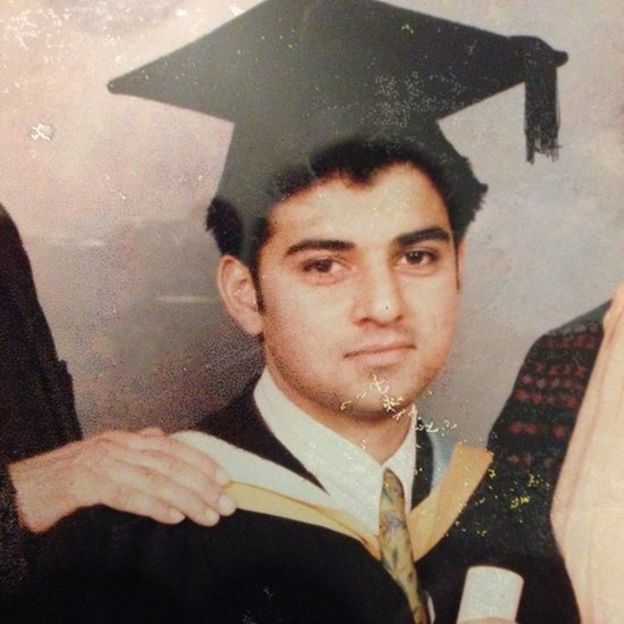

He studied law at the University of North London and put his degree to good use straight away, becoming a trainee solicitor in 1994 at Christian Fisher under the human rights lawyer Louise Christian.

The same year he met and married his wife Saadiya Ahmed, a fellow solicitor and coincidentally the daughter of a bus driver - with whom he went on to have two daughters, Anisah and Ammarah. He also began his 12-year stint as a councillor for Tooting, encouraged by Guyanan-born local activist Bert Luthers.

Just three years later, aged 27, he was made an equity partner and the firm was renamed Christian Khan.

During this time he worked on a number of high-profile cases: he won compensation for Kenneth Hsu, a hairdresser wrongly arrested and assaulted by the police; teachers and lawyers who had experienced racial discrimination; Leroy Logan, a senior black police officer accused of fraud; corrupt former Met Police commander Ali Dizaei; and helped overturn an exclusion order (later upheld on appeal) on US political activist Louis Farrakhan.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The irony of a man who represented people in cases against the Met going on to become the force's chief scrutineer has not been lost on his opponents. Conservative candidate Zac Goldsmith, speaking at an event alongside Home Secretary Theresa May, recently characterised Mr Khan's legal career as "coaching people in suing our police".

He left his law firm somewhat abruptly in 2004, afterwards telling the Law Gazette: "If you're in government, you're a legislator and you have the opportunity to make laws that can improve things for millions of people."

In 2005, Mr Khan fought and retained the marginal seat of Tooting for Labour, one of five new ethnic minority MPs elected that year.

Contemporaries on either side of the political divide remember being impressed by a "fiercely bright" and "persuasive" individual who was "impossible not to listen to".

He combines that sharpness with what is often called his "cheeky chappy" demeanour. He is fond of calling people "mate" and has even done so on the floor of the Commons.

'Voice of reason'

Two months after he entered the Commons, he was thrust into the limelight by the7 July bombings.

When Parliament met to discuss the attacks, he told MPs: "Today Londoners and the rest of the UK have even more reason to be proud of Londoners - proud of the way heroic Londoners of all faiths, races and backgrounds, victims, survivors and passers-by, acted on Thursday; proud of the way ordinary courageous Londoners carried on with their business and stopped the criminals disrupting our life."

In a 2010 Guardian interview, he recalled thinking: "I couldn't hide - and I don't mean this in an arrogant way, but there were so few articulate voices of reason from the British Muslim community.

"There were angry men with beards, but nobody saying, 'Actually, I'm very comfortable being a Brit, being a Muslim, being a Londoner'."

The intervention marked him out as one to watch, but his path to promotion was not altogether smooth.

Mr Khan wore his civil liberties credentials on his sleeve, challenging the government over ID cards and joining 48 other Labour rebels to vote against prime minister Tony Blair's plan to allow the detention of terror suspects without charge for up to 90 days.

He later claimed party chiefs had penalised him by preventing him from visiting Pakistan in the wake of an earthquake there and did not want to give him an office with a sofa.

But the rebellion was not altogether to his disadvantage.

Tony Blair was on his way out, and Mr Khan was able to position himself on the ascendant "soft left" of the Labour party alongside Ed Balls and Gordon Brown.

Sadiq Khan in his own words

"It was a tough school; it wasn't always a bed of roses. But you become street wise, you become savvy and you learn social skills - you learn about how to deal with people." - on his schooldays

"The way allegations of misconduct against police officers are investigated is flawed and inadequate." - as a human rights solicitor

"Although I'd won cases at the European Court of Human Rights, and I'd won cases in the House of Lords and the Court of Appeal, I still couldn't escape the fact that if you're part of the legislature and the executive, you can make legislation that improves the quality of life for literally millions of people." - on leaving law to become an MP

"Today Londoners and the rest of the UK have even more reason to be proud of Londoners - proud of the way heroic Londoners of all faiths, races and backgrounds, victims, survivors and passers-by, acted." - on the 7/7 attacks

"Most people feel nagged by their parents from time to time, but very rarely is it about the future of bus regulation." - on his father

"I sleep in my own bed. When I get home I put the rubbish out and get my girls up to go to school." - on staying grounded

"For the last eight years you've seen a red carpet mayor, somebody who is fantastic going to openings, great with a flute of champagne in his hand. I'd rather roll up my sleeves and fight for all Londoners." - on launching his mayoral bid

When Gordon Brown took over at Number 10, Mr Khan was given his first job in government as a whip and then as communities minister, a move that created disquiet among some other MPs in the capital who had been around for longer.

A post at the Department for Transport followed in 2009 and he became the first Muslim in the Cabinet. This was at a time when there were only four Muslim MPs and he was often confused for international development minister Shahid Malik.

He would go on to claim during the mayoral campaign that as transport minister he had "pushed" Crossrail through Parliament, but the Mayorwatch website has shown Mr Khan only took on responsibility for the project after the relevant bill had become law.

At the 2010 election, Mr Khan's own majority was squeezed to an uncomfortably small margin of just 2,524 votes and Labour was out of government for the first time in 13 years.

In the chaotic months of Labour soul-searching that followed, he again showed a canny ability to ally himself with what was seemingly a lost cause and turn it into success.

True to his Brownite colours, he was chosen as Ed Miliband's campaign manager and helped steer the less-favoured Miliband brother towards an unexpected leadership election victory.

Getty Images

Getty Images

He told the New Statesman afterwards that the night before the result, he told Miliband to "prepare for defeat".

"I learned this from (television series) Rumpole of the Bailey," he said. "Always tell your client he's going to lose because, if he loses, he's expecting it; if he wins, you're the fantastic lawyer who got the victory." However, he added: "I had a feeling we'd done it."

In that contest, as in the Labour mayoral nomination, Mr Khan's support for the trade union movement helped his campaign secure crucial votes.

He was rewarded with the post of shadow justice secretary - a role in which he did not get off to an auspicious start. His first major speech was badly received when he chose to highlight Labour's failings in government, and in then Justice Secretary Ken Clarke he faced an adversary with whom he admitted he struggled to find things to disagree about.

His other brief as shadow political reform minister did not provide much of a chance to shine either, as the coalition needed little help killing off its own proposals for Lords reform and his personal support for changes to the voting system was tempered by his view that the referendum on this - which saw the British public reject change - came at the wrong time.

When Mr Clarke was sacked and replaced with Chris Grayling, however, Mr Khan was able to take the fight to the despatch box more convincingly as a vocal opponent of reforms to legal aid and restrictions on books in prisons.

When the Conservatives later reversed several of Mr Grayling's flagship policies he described it as a "huge climbdown" that showed Labour had been right to resist them.

A surprise choice

Getty Images

Getty Images

Labour's disastrous showing in the 2015 election and the swift resignation of Ed Miliband - the man he had helped to the leadership - could have thrown Mr Khan off-course, but he found a new focus for his campaigning energy.

Just a week after the election he announced he would seek the Labour nomination for mayor. He had already been tipped as a possible contender at least a year but, with typical shrewdness, he had steadfastly refused to be drawn on the subject in public while sounding out MPs and councillors in private to see if he had enough support.

Once he had confirmed his mayoral ambitions, his quest for the nomination - let alone an election win - still seemed like a long shot. Baroness Jowell, who had been MP for Dulwich and West Norwood for 23 years and held a number of senior ministerial positions under Labour, was widely seen as the natural choice.

That received wisdom was upended during the Labour leadership contest, when commentators predicted the influx of new members into the party over the summer of "Corbynmania" could play into Mr Khan's hands. He would take some flak over his role in Jeremy Corbyn's election as party leader, as he nominated him but later voted for Andy Burnham.

In the event, however, Mr Khan came out top as Labour choice of candidate not just with new members but in all three groups who could vote. It was a remarkable victory which, as the BBC's Norman Smith observed on the day, surprised him as much as it did his rivals.

The campaign that ensued was bloody. A former aide to long-time Labour deputy leader Harriet Harman, Ayesha Hazarika, reflected that when Zac Goldsmith - who had a reputation for being decent, attractive and independent-minded - was first picked as the Conservative candidate there was despondency in Labour ranks.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Mr Khan said himself at one hustings that he thought his opponent had been a "nice guy until [Conservative strategist] Sir Lynton Crosby got his hands on him".

Whoever came up with the approach, Mr Goldsmith's campaign focused heavily on portraying Mr Khan as an associate of "extremists" - which in turn allowed Labour to attack the Conservatives for pursuing "divisive, dog-whistle" tactics.

Mr Khan took this to be an attempt to smear him by association because of his religion. The Conservatives insisted they were talking about his brand of left-wing politics - but Mr Goldsmith repeatedly said the Labour candidate had "given platform, oxygen and cover to extremists".

It became a source of such bitter tension between the two camps that when David Cameron stuck up for Mr Goldsmith's campaign at prime minister's questions he found the word "racist" flung back at him from the Labour benches.

While polls consistently suggested Mr Khan was ahead, Labour pessimists and Conservative optimists would remind themselves that Mr Goldsmith was likely to benefit from a Tory incumbency, from lower turnout among groups that tended to vote Labour, and from the under-reporting of Conservative support seen at the 2015 general election.

But those things were not enough - or proved not to be the case at all. Voter turnout was 45%, an increase of 7% on 2012, and it was clear quite early on in the day that Mr Khan had a healthy lead over his Conservative rival.

'Huge moment'

Another London Labour MP born to immigrant parents, David Lammy, told the BBC Mr Khan's election was a "huge moment" and predicted: "If we ever see a black or Asian prime minister in this country I have no doubt they will owe an enormous debt to Sadiq Khan."

Now, the boy from Tooting will have to prove himself all over again.

Love them or loathe them, the mayor's predecessors Boris Johnson and Ken Livingstone - the only other men to have done the job - are political heavyweights.

Even within his own party, Mr Khan has been accused of lacking vision. The perception of him as inexperienced also lingers on.

PA

PA

One close Labour ally pointed out that "unlike Ken, he has held ministerial office - but more than that, he represents the future. Unlike Boris he'll be wholly focused on getting results for London - this isn't just a stepping stone for his career".

She predicted he would be anxious to make good on the ambitious promises he made during the campaign, particularly on addressing London's housing problems.

If that were not enough to be getting on with, he faces a dilemma over how to navigate between co-operating with the Conservative government and teaming up with Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party in condemnation of the Tories.

In this respect he may hope to repeat the tactics of Boris Johnson, who managed to pull off alternately angering and assisting the government.

If he is to succeed he will need to display the same knack for steering his own course as he has shown as a schoolboy, a campaigning lawyer, a backbench MP and a shadow minister.

But those who voted for him will not forget his emphasis on his own disadvantaged background, his speeches about social justice and his promise to be a "mayor for all Londoners".

Comments

Post a Comment